We do ourselves a great disservice when we devalue the power of feelings. The somatic landscape holds much of the information that we seek, and yet so much of how we live prevents us from knowing that. A client once reflected in session, “I used to hate having emotions. Now I know how to use them.” I could have jumped with joy. Country, let’s make this the norm.

When I saw Caitlin Flanagan’s response to what “Grace” shared about her date with Aziz Ansari, I felt nauseous. She made a lot of damaging comments, but the one I’m taking on here is her belief that Grace could have simply left. It is a brutal misunderstanding of the power of feelings, and I cringe knowing that anyone read it and agreed. From Grace’s account, we can pretty safely hypothesize that she was stuck in a freeze response. When neither fighting nor running away are perceived as possible, our parasympathetic nervous system offers up this third option. In extreme cases, it can look like playing dead. It can also look like playing along. Now whether or not that’s actually what happened for Grace, no one can say except her. We can, however, use her story to look at what has become a common encounter.

The #MeToo Movement has been extraordinary for shedding light on the pervasive epidemic of unsafe sexual behavior. We’re finally voicing this deep collective trauma and with each new story, we’re made increasingly aware of the need to understand what brought us here and how to move forward in a way that is healthier for everyone. This is a psychotherapeutic process like any other; it’s just on a very grand scale. So we will be well on our way to healing if we can learn and enact the wisdom offered to us through the psychotherapeutic process. Most relevant here: the need for embodied wisdom.

Historically, we tend to get stuck on deciding who’s responsible for an unpleasant sexual encounter. What therapy teaches us is to be interested primarily in understanding and navigating the interpersonal dynamics involved. Even in the most objectively black and white circumstances, the ability to say whose fault something was is only helpful in bringing us to the next steps: what each person can do moving forward. So rather than looking at fault, we ought to be looking to answer more specific questions like, “Why couldn’t Grace leave?” and, “Why couldn’t Aziz notice her cues?”

It’s very fortunate that #MeToo is bringing us into exploration of these gray areas of human interactions. It’s where some of the most important work can happen, and that’s exactly why it’s so challenging. What’s happening in response to what Grace shared should make very clear how impossible it is for us to quickly lay blame somewhere and move on. The subsequent conversations it has provoked have been a loop of “he should have…” and “she should have…” Often both things are true. But the complexity does not end there, as there is a myriad of reasons that brought each of them- and any two people- to this interaction wherein one person left feeling violated. So it’s time we distinguish between intellectual and somatic understanding.

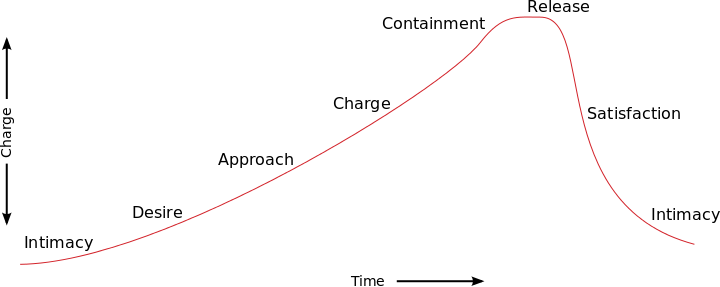

“Somatic” means whole body. The word is used as a way to point to the entirety of an experience rather than to artificially separate what’s happening in someone’s body from what’s happening in their brain. The two are inextricably linked, and that’s extremely important to understand particularly as it relates to sex. Our bodies will tell us right where we are with things, which is vital to pay attention to, because knowing something intellectually is not the end of the process. You can think of it like learning to play a musical instrument. Studying theory is helpful, but you won’t be able to really play until you’ve practiced.

We’ve been more acutely onto this knowledge over the last decade or so. We’re realizing that intellectual insight is limited. It does not automatically translate to being able to do anything with the information. We can understand something, but not believe it. We can know why something is happening, but feel unable to prevent or change it. We can even fully believe something in thought while our body strongly disagrees. Embodied knowing simply takes further work.

When so many people are upset by a topic this disturbing, one of the greatest challenges is finding our common goal in the work. Fortunately, this one is quite clear: we all want safe and enjoyable experiences with others, especially when it comes to sex. Knowing that is an important part of the process, because we now get to address what’s in the way of getting there. Our current roadblock: we’re lousy at attending to feelings.

The experience of feeling unable to do something is, in the moment, no different that being physically unable to do it. This awareness is built nicely into all fields of psychotherapy in the form of verbiage for states like post-traumatic stress, which is a response to a real or perceived threat of injury or death. Fortunately, this knowledge has been sneaking into popular culture in various ways. We’ve finally begun to consider the “placebo effect” a legitimate effect, for instance. And indeed it is. If it has an impact, it’s an effect.

But historically we have been very poor at acknowledging emotions as real, legitimate, and unpreventable. It’s that last one that seems to give us the most trouble, because we can learn to make choices that make particular emotions less likely to surface in certain situations. But this control is limited, and it’s limited even more so than our ability to control something like hunger. With hunger we can eat regularly, eat enough, eat well, carry snacks, and so on. But with emotions, we have far less control because emotions most often surface in response to other people, who are ultimately out of our control. You can be well rested, well fed, and in a great mood and fear will still surface when you nearly hit someone who walks in front of your car. So our greatest power comes in our ability to respond to our own emotions appropriately. And no matter the context, an appropriate response means one that comes from a place of compassion and openness. These are the qualities that allow us to listen to, learn from, and make use of our feelings. Once we can do this for ourselves, we can begin to extend the practice to others.

Now think about that myriad of reasons that, even without knowing their unique backgrounds, allow us to guess at why Grace and Aziz would find themselves in such a confusing and painful exchange. To name what I’m sure is far too few:

- People, especially females, are routinely objectified. Objects are things that we can interact with as we please. The impact we have on them is irrelevant, and so we often don’t even consider it.

- We fail to teach people, especially males, how to interact with their emotions. We will even use shame to suppress them. Since emotions do not long tolerate being ignored, they find ways to get their needs met surreptitiously or violently.

- The above factors create a very dangerous combination. Objects are handy sources for getting our needs met, since they require nothing of us. We don’t have to admit our feelings to them in order for our needs to be fulfilled. So it confuses, scares, and sometimes angers us when an object suddenly speaks up about their subjective experience.

- We teach women that sex won’t be all that enjoyable, and to be polite about that. This was actually written in pamphlets given to women at the turn of the 20th century. That’s only a few generations back for a lot of us, and so its remnants remain strong.

- We are persistently reinforced with the notion that there is a way to successfully manipulate our interactions with others, and that most of it has to do with pursuing and distancing. If we pull back a little, the other person will come pursue us. If we lean in too much, they might distance. They’re distancing themselves because they want to be pursued. You can’t be explicit about pulling back or you’ll hurt their feelings. Most plot lines depend on our belief that we should be indirect. The next time you’re watching a television show, imagine what would happen to the trajectory of the story if just one person were able to share what they were feeling.

It is no surprise then that we have ended up here where one person wasn’t trusting their feelings and the other wasn’t even noticing them. So whose fault was it? Everyone’s. It is collectively our fault. We train our females to resist their urges to fight or flee, and we train our males to fight no matter the circumstances. Most of us contribute to this even though we consciously try not to. It’s my fault for not speaking up last week when someone used the term “man cold.” It’s the fault of every catcaller. It’s the fault of every person who agreed to distribute that pamphlet to our great-grandmothers. It’s the fault of the schools that fail to teach sex ed. It’s the fault of everyone who’s ever said, “You’re just emotional.” We must attend to all of this if we want healthier interactions. Fortunately, we’re already amidst a gender revolution, and I suspect that one of its many gifts will be to draw us away from rigid roles that train us out of our natural states of being.

I hope that any of us could find our way to relating to either person in an interaction like Grace and Aziz’. If any of it seems easy, I encourage you to recognize how you’re devaluing your abilities or taking them for granted. The ability to leave, speak up explicitly, or accurately read bodily cues are all strengths. If they’re strengths you have, figure out for yourself how that came to be, and then help others to develop these qualities. If these aren’t strengths of yours, learn to listen to the subtle cues of your body, and then learn to do so with others.

It is returning to embodiment that brings us health. We need our sensations and emotions in addition to our thoughts in order to understand what’s happening in the moment and to act accordingly.

Further Reading and Resources

Books:

Healing Sex by Staci Haines

Waking the Tiger by Peter Levine

Emotional Intelligence by Daniel Goleman

The Sex and Pleasure Book by Carol Queen with Shar Rednour

Research:

http://usabp.org/research/somatic-oriented-journals/