Beginning my series with a movie in which there is no therapist? Yep. I’m starting with the French film, “Le Fabuleux Destin d’Amélie Poulain” by Jean Pierre Jeunet, because it is beautifully rich with psychotherapeutic concepts. It has long been a favorite film of mine, but the first time that I watched it sans sous-titres, my heavier focus on the nonverbals helped me to really see what it has to offer. I suspect that that was no coincidence. As with much of what I will cover in this series, this work is full of what-to-dos and what-not-to-dos.

Let’s start out with the lovely introductions to the characters. We are invited to know each one of them through these little distilled moments about how they experience themselves and the world. These are the little things that tell us far more about a person than most anything else. Jeunet uses these richly sensory-based moments to give us years of history in one fell swoop. These peeks into such private moments quickly build intimacy between us and the characters. For me, this is reminiscent of the rapport-building that occurs between therapist and client over the first few sessions, and the understanding that deepens between us over time. As with any relationship, it is witnessing each other which draws us closer. And one of the fastest ways to do that is through learning about how someone experiences their body. This is the essence of somatic work. Amélie’s mother experiences the creases in her cheek from her pillow as unpleasant. We relate or we do not, but we also begin to decide what this might mean about her. Amélie surreptitiously dips her fingers into a sack of beans. We relate or not (many of us super do), and again, we have ideas about what this means. It is also these yummy little sensory moments that are why I have called this film very autism-friendly. (If you didn’t know, autism often comes with the superpower of heightened senses. Just like Catwoman.) The film’s visual style is also very important. It seems to give reverence to everything, which affects us throughout the film by keeping us very present and thus tuned into every part of an experience. This mindfulness which Jeunet so easily induces is a large part of the therapeutic process. In order to move through anything, we must be present for it. That makes it very important to have plenty of lovely things to tune into. And for the love of the accordion, is that soundtrack magical. Someone once said to me that it’s as though it makes everything feel important.

The film’s visual style is also very important. It seems to give reverence to everything, which affects us throughout the film by keeping us very present and thus tuned into every part of an experience. This mindfulness which Jeunet so easily induces is a large part of the therapeutic process. In order to move through anything, we must be present for it. That makes it very important to have plenty of lovely things to tune into. And for the love of the accordion, is that soundtrack magical. Someone once said to me that it’s as though it makes everything feel important.  This too is a quality of the therapy space. Everything is (or is aimed to be) treated with importance, because it often is. During grad school, we learn to become therapists by practicing the therapeutic process on each other. Because the environment is intended primarily as educational, we are encouraged to pick real, but relatively surface-level vignettes to share from our lives. Regardless, things inevitably deepen. You realize that the way the bus driver spoke to you irked you because she sounded like a critical voice from your past. You find that the soft touch of the person who gave you your change at the coffee shop brought you into the present moment. And it is all these snapshots of the Self and of experience that I am after as a therapist.

This too is a quality of the therapy space. Everything is (or is aimed to be) treated with importance, because it often is. During grad school, we learn to become therapists by practicing the therapeutic process on each other. Because the environment is intended primarily as educational, we are encouraged to pick real, but relatively surface-level vignettes to share from our lives. Regardless, things inevitably deepen. You realize that the way the bus driver spoke to you irked you because she sounded like a critical voice from your past. You find that the soft touch of the person who gave you your change at the coffee shop brought you into the present moment. And it is all these snapshots of the Self and of experience that I am after as a therapist.

One of the aspects I most appreciate about this film is the therapeutic relationship between Amélie and Dufayel. It is the nearest to an accurate portrayal of the therapist-client relationship that I have ever seen. It even demonstrates a specific modality in art therapy. Dufayel invites Amélie’s interpretation of the girl with the cup, asking gently investigative questions along the way. This pulls from her more deeply articulated thoughts, making her own process of relating to others a more conscious one. When he offers an accurate but risky interpretation, “You mean she’d rather imagine herself relating to someone who’s absent? ” she’s a bit miffed, as any client might be. But the seed is planted, she considers it moving forward, and it later blossoms into a deeper understanding of herself. This happens constantly in the therapy room. Dufayel is also a therapist to Lucian. He beautifully demonstrates somatic work by having Lucian express his anger at Colignon through a little rhyming. putting his body behind his thoughts. What’s more, he helps him to contain it. He cuts it off when Lucian begins to spiral, for catharsis without a holding space is nearly useless. We also get to see what happens when Dufayel pushes his agenda a little too hard- something we therapists work hard to avoid. When Lucian won’t stop talking about Lady Di, rather than following that thread, Dufayel explodes with frustration. Luckily their relationship is strong enough that Lucian returns to it, as does Amélie. Therein lies most of the healing in therapy- the experience of repair after a rupture in a relationship.

more deeply articulated thoughts, making her own process of relating to others a more conscious one. When he offers an accurate but risky interpretation, “You mean she’d rather imagine herself relating to someone who’s absent? ” she’s a bit miffed, as any client might be. But the seed is planted, she considers it moving forward, and it later blossoms into a deeper understanding of herself. This happens constantly in the therapy room. Dufayel is also a therapist to Lucian. He beautifully demonstrates somatic work by having Lucian express his anger at Colignon through a little rhyming. putting his body behind his thoughts. What’s more, he helps him to contain it. He cuts it off when Lucian begins to spiral, for catharsis without a holding space is nearly useless. We also get to see what happens when Dufayel pushes his agenda a little too hard- something we therapists work hard to avoid. When Lucian won’t stop talking about Lady Di, rather than following that thread, Dufayel explodes with frustration. Luckily their relationship is strong enough that Lucian returns to it, as does Amélie. Therein lies most of the healing in therapy- the experience of repair after a rupture in a relationship.

Amélie shows us how others are sometimes unable to join us on a new path. Inspired by the discovery of the cigar box, she tries to engage her father in a conversation about it, but she’s met with the same ol’ clueless reaction he always seems to have to her. Just as we all feel when a parent disappoints us in a familiar way, Amélie’s enthusiasm wanes a bit. Fortunately, she trusts her gut and moves forward with her idea regardless.

As we grow, we often become bolder and welcome new experiences. Amélie demonstrates how we sometimes we misuse our strengths as this is happening. This can occur pretty easily if we haven’t yet become aware of our go-to defense mechanisms. When she is pushed over the edge with anger, she uses her cleverness, creativity, and insight to cause Colignon distress. We even got to see her do this as a child. Powerless, and without her parents to step in, she found a way to defend herself. That was pretty ok for her as a kid, but as an adult, its passive aggressivity is not very appropriate. A child meddling with someone’s cable connection is one thing, but an adult meddling with all sorts of things in another person’s apartment is straight up illegal and unethical. Now, perhaps it was a catalyst for change for him, but I never advocate for abusing someone. And inadvertently causing pain is the sort of thing that happens when we try to use the defenses we learned as kids on an adult scale. Rather than scaring someone out of their comfort zone, in therapy we aim to invite them out. This can happen through various means, and I’ll share a tried and true experience articulated by psychoanalytic theory.

With Mr. Poulain, we see the concept of a “transitional object” in action through the well-crafted little lawn gnome strategy Amélie uses on him. In short, a transitional object is something that links us with  the external world in a safe way. We can use it for both comfort and fantasy, and it helps us to move through a difficulty and develop some part of ourselves. We learn early on that Raphaël feels an affinity with the gnome, and we surmise that there may be something to the timing of his pulling it out of the garage. Knowing this and that he wishes but fears to travel, Amélie makes use of the connection and shows him what’s possible. Through this and at this own pace, he is able to come to traveling himself.

the external world in a safe way. We can use it for both comfort and fantasy, and it helps us to move through a difficulty and develop some part of ourselves. We learn early on that Raphaël feels an affinity with the gnome, and we surmise that there may be something to the timing of his pulling it out of the garage. Knowing this and that he wishes but fears to travel, Amélie makes use of the connection and shows him what’s possible. Through this and at this own pace, he is able to come to traveling himself.

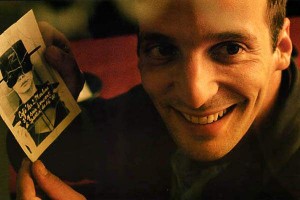

Onto a big one. Sometimes we can’t yet handle what we ask for, and this can leave us feeling like a shell of a person. We do a bunch of work to get something, and then find that we don’t know how to move forward from there. Amelie’s “strategies” work for Nino. He’s intrigued, and he comes to see her. But she finds she doesn’t know how to be seen, and she loses herself a bit. In psychotherapeutic terms, we call this fracturing. It’s the experience preceding what we call “pulling ourselves together.” One of the reasons that this fractured feeling occurs is that our strategies often do not extend from our true selves. We aren’t actually being authentic, and sometimes even we don’t realize this. So when our attempts to connect with others work to draw someone in, there can be a real sense of having tricked them. We worry about what will happen if we ditch those strategies. Do they love us for us? Or because of only what we show them? It cheats us out of getting to actually experience what we need even if it’s right in front of us. So we often choose to go on wearing a mask of sorts. And  Amélie even wears actual masks! When Nino asks, “Is this you?” it doesn’t feel right to say yes, because it isn’t her. Not really. When he tries to call her on it, it’s worse. She can’t know yet that he doesn’t need her to wear the mask. Frankly, he might not know yet himself. But we suspect this to be the case, because like Amélie, Nino has a deep appreciation for uniqueness and authenticity. So we feel for her all the more when having rejected being seen by Nino, Amélie melts into a puddle. We’ve all been there.

Amélie even wears actual masks! When Nino asks, “Is this you?” it doesn’t feel right to say yes, because it isn’t her. Not really. When he tries to call her on it, it’s worse. She can’t know yet that he doesn’t need her to wear the mask. Frankly, he might not know yet himself. But we suspect this to be the case, because like Amélie, Nino has a deep appreciation for uniqueness and authenticity. So we feel for her all the more when having rejected being seen by Nino, Amélie melts into a puddle. We’ve all been there.

Even with all the empathy we have for her, notice how even we begin to tire of her strategies. We want her to find love, so watching her use the same old technique becomes upsetting for us and everyone else who loves her, because we know it won’t work.

That brings us to a really big one about relationships. Having similar childhood wounds help us to bond to each other. I find it to be one of the most beautiful aspects of a healthy partnership, though sometimes it can cause a lot of strife. But we get to see a heartening example of it in Amélie and Nino, who are known to have similar childhoods. The line is, “When Amélie had no friends, Nino had too many.” Both of their experiences are versions of being unseen. Amelie is somewhat invisible while Nino is seen inauthentically. Both experiences can leave a person preferring solitude, or to be an outside observer of others. They can also cause a person to be tuned in to the unique expressions of others. Their coming together has so much to do with their respective recognition of the need to be seen and known by another person. And just as it is with real live people, one of them (Nino) is willing and able first, which can helpfully pull the other in as well. These last two pieces- the masks we wear and wounds we share with our loved ones- are two of the central points of focus in therapy. It is eloquently outlined by just what my favorite Rumi quote describes: “Your task is not to seek for love, but merely to seek and find all the barriers within yourself that you have built against it.”

These last two pieces- the masks we wear and wounds we share with our loved ones- are two of the central points of focus in therapy. It is eloquently outlined by just what my favorite Rumi quote describes: “Your task is not to seek for love, but merely to seek and find all the barriers within yourself that you have built against it.”

I could go on about this brilliant film. There’s the metaphor of Dufayel’s fragile bones, Nino’s externalized inner monologues, and the projection onto the photo booth repairman. There are examples of stimming, splitting, somaticizing, agency, and all sorts of other goodies. It truly is a rich layering of allegories within an allegory. But watching it is far more fun than my covering every aspect of what I believe it has to offer. If you have questions or further interest, I welcome your comments.