When I first met these guys, I was instantly struck by their magnetism. They were cheerful, handsome, and they both make great eye contact- a trifecta of appeal. I felt at once welcome in their presence, and energized to be on my game, for these two beckon to really see you. They are on a select list of people to whom I reacted with, “ohmygod I wanna be friends with you.”

When I first met these guys, I was instantly struck by their magnetism. They were cheerful, handsome, and they both make great eye contact- a trifecta of appeal. I felt at once welcome in their presence, and energized to be on my game, for these two beckon to really see you. They are on a select list of people to whom I reacted with, “ohmygod I wanna be friends with you.”

As we became friends, I thought for a while that they might be a couple. When I realized that they weren’t, I was blown away in a thoroughly delightful way. If their epic level of closeness wasn’t due to romance, this meant that I had before me an astounding example of healthy male friendship. These guys adore each other, and they aren’t afraid to show it.

Because of them, I hold the capabilities of all friendships to a much higher standard. And believe me when I say that I always thought deep intimacy was possible between male friends. I’d just never really seen it until I met Jordan Huxley and Nick Westbrook.

Nearly all of my male clients, regardless of orientation, have expressed to me a desire to have more fulfilling friendships with other men. Often what is sited as the barrier is all the other men. Way too many of them believe that they are practically alone in wanting this. And the insistence of their female therapist that this isn’t the case makes only so big a dent in this belief. So Nick and Jordan graciously agreed to shed some light on how and why they have gotten so close, and how the other menfolk can do the same.

So tell us about how you met. What did you each think of the other?

Jordan: This is a story we love to tell, mainly because it seems so iconic that we’re the best of friends and initially didn’t like each other. I was going to school in New York and living in a dorm in Brooklyn. I liked to hang out by the side of the building, chatting with friends, sometimes playing music. I had made a lot of friends that way, simply being around and meeting new people. A mutual friend of ours, whom Nick had grown up with, introduced him to me one day, when I was outside playing a little music. The way he likes to tell it, I was this hip socialite, completely surrounded by adoring friends, but for me, it was more akin to enjoying a crowd. He, on the other hand, looked like the epitome of cool. A spitting image of James Dean you might say, with his collar popped up and a cigarette and earrings and this look on his face like he didn’t need to prove anything to anyone. So again, we both thought that the other person thought they were hot shit, but it turns out that we were both just attracted to the energy of the other person.

Nick: Haha! We love telling this story. The last time we told it we were a little tipsy—maybe a lot tipsy— and we acted it out with an exaggerated performance of when we first met. The extra drama of us telling the story together is that we both have completely different perspectives on it. I thought Jordan was too cool for school and it made me anxious, and he felt the same way about me… It was a fall afternoon at the Brooklyn dorms for the New York Conservatory for Dramatic Arts (or something like that), where Jordan was going to school. A former friend of mine from Georgia had just started there, too, and he was showing me around the neighborhood. My first impression of Jordan was of seeing him sitting up against the exterior wall of the dorms with a half circle of college students around him, and I swear I’m not exaggerating here, the dude was basically glowing. He was pretty clearly the center of attention, and he was pretty clearly settled into the role. He was smiling and he seemed very charming and confident, two things that I tried to embody, myself, but when I saw them in other people I could easily distrust or feel threatened by — at least in those days. I was only twenty. Anyway, I thought he looked like a really cool guy and in my young silly way I immediately took that to mean that he was probably a stuck up jerk, like the other popular guys I’d met during my one, mostly unpleasant semester in college. Sometime that day or that week I heard he was screening one of my favorite movies, Jaws, on a… ahem… projector in his dorm room for his … ahem… many adoring friends. What a jerk! Of course, I just saw him as an alternate reality version of myself… the one who had prospered in college and even ended up with a projector and a bunch of friends… and I guess I just couldn’t deal with it! Honestly, I’ve never even realized that much about it until now. We usually stop the story short with “I thought he was too cool! I thought he was too, cool, too!” and then fast forward to the important part… the fateful second meeting. I’ll just put that part below, since it goes with the next question.

When did it become clear to you that your friendship was on an epic level of awesomeness?

J: I would have to say that it was clear to me that our friendship was something genuinely special and interesting when we had our first legendary Tuesday. We had already been hanging out for some time, since we had decided to write a screenplay together. But as we got to know each other and our enthusiasm began to grow mutually, we could tell that we were going somewhere. And one day, a Tuesday, Nick invited me out to a place called Fabulous Fannys. It’s a vintage and antique eye and headwear boutique and I was immediately enamored. I love classic style, and he knew. There was a classic fedora he had his eye on, a brown Stetson, and he looked at me and told me that we needed to get matching ones. It was expensive, one of the more expensive articles of clothing I’ve ever bought, but I knew that it was worth it. Sometimes you gotta take the leap. We walked out with our new hats and new confidence. It called for a special occasion, so we caught a 2-for-1 martini happy hour and proceeded to laugh and talk about everything. The city faded into the background and I felt very much at home. But what was more amazing was that the people passing by kept commenting on our hats and how great we looked! Even a cabbie rolled down his window to let us know how stylish we were! It seemed like the world was proverbially our oyster. I just had never really felt so adult, and confident, and at home with a single other person like I did that day.

N: Like, immediately. Not even kidding. It was in the air. The stars and planets were aligned. We knew we had stumbled into something grand and life changing. We had seen each other a couple of times after that first meeting and gotten along fine, but following a falling out with our mutual friend at Jordan’s school, I stopped coming around and we didn’t see each other for a year or so. Then, one fateful fall evening, when I had little to do but put on my long coat and walk around rolling cigarettes and hoping to look cool, I took the train over to Brooklyn heights for a nostalgic kick and went in for a drink at the Pub where all the underage kids from the dorms used to drink every night. The bartender might remember me, at least. I didn’t really expect to see anyone I knew, and I especially didn’t hope to run into my former friend from Georgia, but I was surprisingly, pleasantly, surprised (read it again, it works!) to see Jordan sitting at a booth in the back. Something about his energy that night just put me in a great mood, and this was the first time we realized how contagious and exponentially self-perpetuating our energies could be together, because we started drinking together with his other friends and we were telling stories and talking about movies and more or less hanging on each other’s every word. And we had a couple whiskeys and went for a couple smokes and by the end of the night we were out there by ourselves and I felt compelled to go out on a mighty limb, but I wasn’t scared and I know it wasn’t the whiskey that gave me the courage, it was something deeper and more substantial.

Our beliefs are such a guiding force in how we live our lives. What did you learn growing up about male friendship?

J: I think initially, from school at least, I learned how male friendship is very much about the things you are both interested in. And discussing, debating, and detailing the differences in your opinions about those things. I observed as well, that many other male friendships were very rough, kind of braggartly, a lot about showing the other one up. I never felt comfortable with that, and I knew that there was a fundamental part missing. As a consequence, I had maybe two or three good male friends, but lots of female friends. My female friends seemed to want to talk about more things, like emotions for instance, that my male friends never seemed to want to get into. In my family I also felt a kind of resistance to discussing any feelings that weren’t in the norm. A kind of unflappable personality was recommended. But I knew there had to be someone with whom you can discuss and share all these things. It just seemed as if close male friendships were innately hostile and unforgiving.

N: Everything I feel about male friendship starts with my dad. He and my mom divorced when I was too young to remember much, so all of my early memories of he and I are of a very close, affectionate, and exclusive dynamic. We would spend time with my grandparents and aunts and uncles and his friends, too, but many of my most vivid and favorite memories are of us by ourselves in this house in north Georgia, out in a very rural part of the county, where we lived on five acres of forest and field. There was about six months where my mom was living in South Carolina and she was also recovering from a bad wreck so it was just me and dad at home, and he was single then, too. We did everything together, and everything we did was fun and intimate— we built campfires in the woods several nights a week, we went on long night rides on his Harley Davidson, we took the ford bronco four-wheeling off roads, through creeks and large pools of mud, we took a vacation to Florida in the mustang with the top down, we went to biker bars and went across state lines for fireworks. He treated me like we were best friends and father and son at the same time. And that’s what we were. My grandmother died when I was only five, after which I spent a lot of time with grandfather at his house, and it would be just the two of us while my dad was at work. So I was spending a lot of quality time with the two most important male figures in my life and they both made me feel that way, like a great companion. I slept in my grandfather’s bed with him after my grandmother passed, and we were never lonely. I remember my mom’s third husband being really strict and telling me to call him sir. I got in the habit of it and the first time I called my dad “sir” he looked at me like I’d said a bad word! He knelt down to me and he said, “You don’t have to call me, sir. We’re friends. Buddies don’t call each other “sir”.” I look back and I think it’s miraculous, now, because he had a very bad relationship with his dad, but he was going to break the chain at all costs. He was going to make sure that we had a great relationship, one of mutual respect and trust and love. And he never forgot to be stern when he needed to be, and I wanted to be good because I loved him so much, instead of because I was scared of making him mad. Sorry, I’m getting a lot out, here. But I know that having the concepts of friendship and close love between men fused together… of being each other’s world entire, even if briefly… is what eventually allowed me to recognize and believe in the potential of my friendship with Jordan. It’s hard enough to embrace something and not be scared about it… but the next step, the one I think that’s the hardest to find, is to go past that and just know it. Jordan and I have always just known that we were destined to be friends indefinitely, and to try to do great things together. I’m lucky that I got to know that kind of certain love at such an early age.

Are you breaking any of these “rules?”

J: Absolutely. I’ve learned through being friends with Nick that although it’s okay to keep a confident positive air, you need to be willing to discuss what’s actually going on with you. The more you keep under the surface, the more you bottle it up, the more it will express itself negatively. I also know now that it’s okay to be inquisitive about how someone is feeling. And that you need someone to talk to about the deeper questions of your existence. And that aggression and hostility are never the correct answer to any frustrations you may have. And that the more you cut under the bravado, the more you know yourself and your friends.

N: No, I don’t think so. Jordan and I are pretty much operating at what I see as the full potential of friendship, at least with this number of years under our belt.

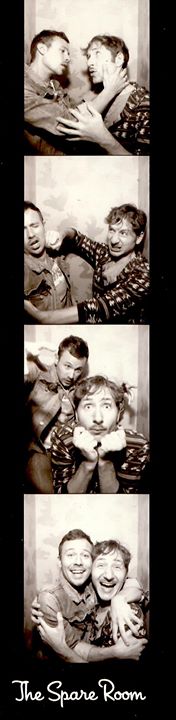

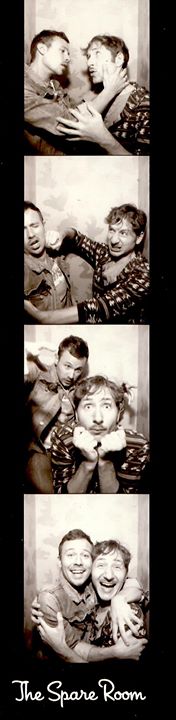

What is it like for you when people mistake you for a couple? How often does it happen? How do you react to them?

J: Oh I don’t care if people mistake us for a couple. It happens occasionally, to be sure, but I for one, am flattered that we are close enough that people either think we are a couple or, more often, brothers. It doesn’t occur to them that people can be as close as we are without being one of the two. I also genuinely love surprising people and breaking down their expectations. When people find that their assumptions are wrong, that is usually a positive thing, in whatever small way.

N: It doesn’t bother us at all. We sort of welcome it in a very self aware and comical way. It might be hard to believe but I think it makes us proud. Again, that’s possible because we have the confidence of absolute knowledge. We don’t think we’re great friends. We know it. When you know something completely it doesn’t matter what anyone else perceives, and I think it’s the nature of our combined spirit to not only not let it bother us, but to let it be something fun and a source of pride for us. If people can see us interacting and only assume that we’re something different than incredibly close friends, then that makes me feel like our friendship is progressive. I don’t know if I’d say it’s cynical to dismiss it as rare or not normal, but I’d say that’s selling it short, and it’s selling all friendship short! To say that ours is weird is selling short the potential that’s actually there that no one’s thinking about or choosing to see. Does that make sense? I guess that’s why I see it as progressive instead, because I like to believe that in the future more friendships could be like ours. For now, it just makes me proud!

Have you ever been discouraged from being so close or showing each other so much affection?

J: Yeah, but really only out of the jealousy of others. I won’t get specific, but there has been a time or two when another person grew resentful or jealous of our closeness and tried to cause dissent between us. It didn’t work, to say the least.

N: Um… Not really directly. We’ve encountered negative reactions to it, but those always seem to be projections of insecurities that arise from within people outside looking in at us. No one’s ever tried to discourage us in a direct way, like telling us we’re being impertinent or making people uncomfortable. But people have felt jealous of our friendship before and we’ve seen it bum people out. We’ve also seen people view it as an unfair advantage in social situations, like where a group discussion is happening, because we tend to agree on most things, not all things, by any means, but most things. And so we can each present an opinion in a group with the confidence of knowing that we won’t be left to fend for ourselves if there’s opposition. That’s great for us, and it comes from a place of love and support but sometimes, you know, people are again threatened by it. It doesn’t happen often though.

What are your fights like? How do you resolve disagreements?

J: I would say, of the few fights we’ve had, the root was a genuine misunderstanding (aren’t almost all fights?). Situations arise where one of us might think we knew what the other felt about something, only to be surprised by the answer. And as soon as you can take a step back and realize that the other person, whom you know so well and hold dear, isn’t purposefully trying to make you feel bad, then you can talk about why you felt a certain way and make peace.

N: Our fights are always very sudden, very intense and emotional, and resolved relatively quickly. If we are fighting the reason is almost always that one or both of us is compromised by something external or internal, but separate from our dynamic. Sometimes it is too much whiskey. Sometimes it is tequila. Sometimes we are stressed, and we take on extra guilt from not being able to immediately make the other one feel better, and that guilt becomes more stress, and that leads to tension. So when that happens it’s still stemming from the seed of love and support, but we’re both human and we need to feel our emotions in our own way. And sometimes we can cheer each other up and sometimes we need to work through our stuff but this expectation to cheer each other up is still hanging in the room and it deflates and feels awkward and heavy and that can be a sort of tension. Sometimes a tension builds up because one or both of us isn’t willing or ready to talk about what is going on inside. Like a pebble in your shoe, something tiny can become something very upsetting. Sometimes I am not being honest with myself about how I’m really feeling and I’ll have myself convinced that i’m feeling great and then Jordan sees me and I know he knows I’m not alright and part of me resents him for breaking down my illusion. But he just knows me that well. That goes both ways sometimes and it’s very hard to be in that situation. In that situation, someone asks you if you’re alright and it sounds like an accusation when it’s really not. But we both have the tell tale response that shows we’re hiding something and usually we talk it out and feel better. We always talk things out after we’ve gotten mad at each other in a very sweet and constructive way, because we both really want to rush back to that feeling of harmony and oneness. Now that i think about it, it’s really when I’m not feeling harmonious with my inner self that i start to feel the disconnect with the people around me, even Jordan. It’s like I have to go through the thing I’m feeling with myself with him too in order to reset everything and work on feeling better. He helps me in ways he doesn’t even know, I swear.

What was one of your favorite moments together?

J: Wow, I have no idea where to start. Okay, actually I’d have to say that the most memorable and amazing experiences I’ve ever had at any time, was a road trip we took from his home in Georgia to my home in Idaho and then down here to LA. It was a long journey, but it proved to me not only the kind of deep friends we are, but that life can be simply amazing. The simplicity of how we lived on the trip and the vastness of the land we were traveling across gave me a glowing feeling inside that I still yearn for again. And I’m not sure I’ll ever be able to feel that way again, in the same way as I did on that road trip. But there’s been so many! I’m just gonna name off a whole bunch: When we used to sit in his car and record our late-night drinking conversations; when we go up north to the hot springs and talk about life; when we ran an under-ground restaurant out of our apartment; when we used to sit in his apartment stairwell eating pizza and reading each other our original writings; the epic Tuesdays.

N: Man, that is tough. There was that famous Tuesday in New York… but thinking of where we’ve been at these last couple years, the moment I’m thinking of was one night when we decided to drive up state for the night, just to get out of the city for a day and a half, and we did a few wine tastings in Solvang and got a good little buzz on, then we had a cocktail at a little Chinese restaurant and met some nice people- maybe they thought we were a couple now that I think about it, who knows- but we had to make it to this spa hotel by 11pm so we get an outdoor mineral spring jacuzzi tub and a bottle of wine (we actually called it our “gay-cation, so I guess we’re okay with it!). anyway, driving north up the windy road from Solvang with a buzz on and rushing toward our jacuzzi we started talking about how good it felt to get out of town together and to be free to just be ourselves and just be our pure, complete selves, like we only are when we’re together, and we got so excited about how good it was and how lucky we are that we just started shouting things in the car. It was cathartic and funny at the same time and it felt amazing to just have someone i knew and cared about that much just shouting in a car with me about how good life felt at that moment. My throat was sore the next day but it was worth it. And we had a nice time in the jacuzzi. We smoked a joint in the car and wandered around the grounds and gardens waxing existential about space and history and aliens and creatures and everything else.

A lot of hetero men tend to make their romantic partner their sole source of emotional support. Does your friendship change when one or both of you are coupled?

J: We certainly have less time to spend together. But not much changes in way of our relationship, simply that when we do see each other, we have more to talk about and feel the need to make that time count a little bit more. And frankly, I don’t feel as if I can have complete 100% emotional support if Nick isn’t there. It’s about balance; I don’t think one person should be your entire support structure.

N: No, as a matter of fact I think if anything it’s changed for the better, because when we’re in relationships we appreciate the others support more than ever. And we get more distance and sometimes that’s a good thing, because we’re prone to missing each other and that’s very lucky when you live and work with someone, isn’t it?

I’d call you both very comfortable with expressing emotions. Will you speak to the topic of crying?

J: Well, crying is damn good for you every once and a while. Obviously, because of societal norms, we both felt self-conscious about the fact that, say, if we went to see a powerful movie and it effected us, we would cry. But I think that freedom, and seeing that we both loved self-expression and storytelling to such a degree that we could allow ourselves to fully feel those emotions, made us closer friends anyway. And if you are friends with someone long enough, eventually you will go through a rough time, and it feels good to let it out. If you don’t feel that support, or feel judged, then something is being held back.

N: Sure, Jordan and I have cried around each other several times. I can’t count how many, but each has been treated as a something significant, and yet not out of place. We always treat it as something natural and easy but we also don’t gloss over it or ignore it. We’re completely comfortable crying around each other. Jordan was my main source of support when my dad passed away, and he saw me cry many times during that period.

A lot of close friends don’t do so well living together. What has that been like for you? How do you manage it?

J: It’s been great! I honestly cant see myself living with someone else in the immediate future. With anyone, there’s a learning curve when you live with them as to what their routines are, what they like to keep clean, how to manage your personal space and public spaces. It just happens that we have a lot of the same aesthetic so we both agree on how the spaces should be utilized. As long as you communicate, and in a way that is meant to be productive, then things usually go swimmingly. And now we’ve lived together, all told, for 5 years.

N: It has literally been a dream come true. I mean we used to day dream and talk about it all the time in New York, where we got to live together only very briefly and under haphazard circumstances, really. But here we’ve really got what we always wanted. A space that feels like home and has so many great memories of having fun and being productive. We’ve had the occasional point of contention regarding basic room mate stuff, but it’s very rare. We have a very hard time doing our own thing when we’re both home. We always end up just doing whatever we’re doing together. It’s funny because at this very moment we are both at home and we are both in our own space doing our own thing, but we’re both doing the same thing because we’re both answering these questions. So even though this separateness seems like a rare exception, it isn’t because we’re still sort of doing it together. Anyway, we don’t get that tension from interrupting the other persons mojo or vibe, because we’re always wanting to do things together. We also have different work schedules which seems to work out in at least that aspect, we can rely on having the space to ourselves sometimes.

You do so many projects together. Your short videos, for instance, destroy me- they are so endearing. What makes it possible to work together?

J: Our minds are very much in the same places most of the time. We’ve talked so much about what interests us, what influenced us as kids, and what our artistic temperaments are like, that it’s very easy for us to talk on a topic or an idea and immediately see what the other person is talking about and where they’re coming from. But we don’t back down from each other’s critiques either. We don’t always agree artistically, but thats how you learn and get better. We are both sensitive to each other’s emotions, especially when working on a project, so sometimes, especially when it comes to me, I can get hyper-sensitive about something, but as long as we talk through it, it always gets resolved. And sometimes that means walking away from the idea for a while and then coming back at it with fresh ideas.

N: It doesn’t even seem possible. It seems absolutely inevitable. That’s just our dynamic— it’s very spontaneously creative. When we’re together we’re always on the verge of creating a little fantasy or a little story based on whatever’s nearest, like what’s on tv or what we’re talking about. We like building stories together and our brains sync up very easily so as soon as one of us has an idea the other is already building on it or going with it. There’s rarely the anticipation of waiting to see if the other person likes the idea. One of has an idea and immediately it’s our idea and we’re trying to rock it as best we can. If that freedom comes from anything in particular it is probably the lack of judgment between us. We can come up things so freely because there is absolutely no fear of judgment.

Do you ever get sick of each other?

J: Nope! I feel like there is always something that can be shared or talked about. Now, that doesn’t mean that I don’t also crave time to myself. I need a sense of solitude once in a while, but that hasn’t anything to do with Nick. I’d just as much rather go do something fun with him if the opportunity arises.

N: We’ve gotten a little cabin fever before. And like i said before, we let tension get the best of us sometimes, but no i don’t think it would be accurate to say that we ever get sick of each other. We can drive each other a little bonkers sometimes, but that’s not the same as feeling like we are sick of each other. I’m not being satirical when I say this: I can’t imagine ever feeling like I’ve gotten too much Jordan. Maybe I need time to myself sometimes but we’ve never been in that place where we don’t want to be together and in a good mood.

What do you recommend for other men who want to have deeper intimacy in their male friendships? How do you suggest that men like you find each other?

J: I would have to say that you need find someone whom you can relate to. Similar interests, upbringings, aesthetics. Then you need to be able to open up to them and trust them. And get yourselves into situations where you have to rely on each other. And then talk about everything. No holds barred. Even then, sometimes it can be difficult to become close friends. But if you both want that kind of friendship, I can’t imagine why it couldn’t work. Just remember that you are both probably meant for great things, especially if you work together.

N: I think the first thing would be to remove negative reinforcement. It’s okay for friends to jeer at each other in a playful way if you both really know where you stand, and that you stand in a place of love and support, but the biggest hurdle I see is men being very judgmental towards each other, probably because they’re afraid of being judged, and it all gets hidden and poorly disguised as humor. But in my experience the best humor is the good humor that comes when you’re comfortable and feeling safe. I think men being too hard on each other and not being honest with each other about how they feel is part of a different kind of self-perpetuating cycle — where guys are preemptively judgmental or defensive because they really don’t want to be judged or maybe they have been and they didn’t have anyone to talk to about it. I think you really have to just do the thing from the old PSA— be the kid who makes saying no to drugs cool. You know how that kid makes saying no cool? He owns it. He’s not scared. He’s confident and that really is cool. I want guys to start talking about how they feel like it’s not even a big deal… It can be simple, it can be colloquial… just “man, we are awesome friends. cheers to that,” other guys start doing it, one day it’s totally cool to just talk about how you feel. And when you feel safe being honest maybe you start feeling safe in who you really are… and then maybe sarcasm starts to take a hike. I would really love that. I think sarcasm is really damaging when it’s not in a safe place, and I think it’s really great and really important to have that safe place be as rock solid and indefinite as a friendship.

Where can we cyberstalk you?

N: Well, all of our fun videos together are on our Vine and Instagram accounts. I’m on Vine as Nick Westbrook and Instagram as Jabbathemuttonchops; Jordan is on both Vine and Instagram as Huxglyph. I also have a website with my poetry at Tinythingsforyou.com, an. a channel on YouTube called Honey Butter Culinaire, which is a cooking show I shoot at home.

Because I was so moved by this interview and because answering my questions left Nick and Jordan with even more to say, we did a second interview together. So keep an eye out for my follow-up article, which will include further discussion of the implications of this epic friendship as well as tips for how to really get cracking on creating this for yourself.